If we want to show that it's a dental version of, we use the ̪ mark, like.

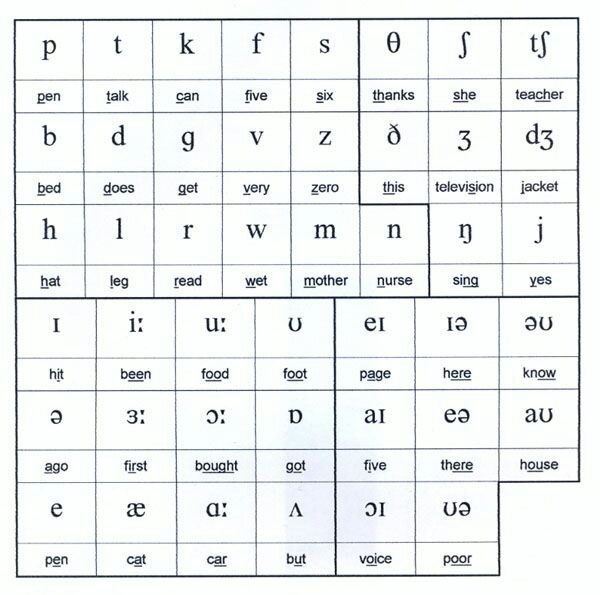

But it's not specifically on the chart, because we use a variation on one of the symbols on the chart for that. For example, can you stick the tip of your tongue against the back of your teeth and stop all the air? You almost certainly can, and many languages do have that stop sound. What about the sounds that are judged possible, but aren’t on the chart? Those are the tan parts of the chart, and even if they're empty, they represent places where we could, make speech sounds, at least potentially. So making a stop at those three spots and allowing air out are just incompatible: that's why we say those sounds are impossible. Stopping air at those points precludes it from getting any farther. Air can't get past there and into the nasal passages in order to make a nasal sound. If you try to stop the airflow at the pharynx, the epiglottis, or the glottis, you run into a bit of a problem. That means that the air doesn't have any choice but to go out through your nose, which gives the nasal quality to these sounds.īut unfortunately, that doesn't work for anywhere behind the uvula. Normally, nasal stops like and are made by totally closing off the airflow through the mouth at some point, like at the lips for, or at the alveolar ridge behind your teeth for. Let's consider, for example, the pharyngeal, epiglottal, and glottal nasal sounds. It's never, ever going to be part of anyone's speech, because we're just not configured to make them that way. Those are places where phoneticians can definitely say that no one could possibly make this sound. The next thing to consider on the chart are the different colorings. Since the place and air flow measures are the same, we keep them together on the chart, and just separate them left from right. That's voicing, and that's what the difference is between those two sounds. You can feel the vibrations in your throat. Nothing’s really happening, right? Now, switch over to carrying a sound. So, say, make an sound and hold it for a bit, while your fingers are on your throat. We'll talk about this in the future, but an easy way to check whether voicing happens is to physically feel those vibrations by putting your hands on your throat.

So what exactly is voicing? It's whether the vocal folds, those little membranes in your larynx, are set to vibrating or not. So, say, let’s look at and - they're both produced by putting the lower lip close to the upper teeth and blowing air past it noisily, but for, there's no voicing, and for, there is. The chart is set up such that sounds that don't have voicing in those pairs go to the left side of the box, and ones with it go to the right. These sounds are produced in the same place, with the same type of airflow through the mouth or nose. First, you'll note that a lot of the boxes have two different symbols in them. The chart has lots of information on it! Let's talk about a few things here. Let's start off the discussion by taking another look at our consonant chart. This might seem like a lot, but once you get familiar with it, the information just jumps out at you!

#IPA TALKING ALPHABET FREE#

Finally, the IPA consonant and vowel charts themselves actually tell us about where in the mouth the sounds are being pronounced, and for the consonants, they also tell us how open and free the air flow is through our vocal tracts. And depending on what we want to be noting down, we can either stay just at the level of the phonemes themselves, or we can add extra detailed information. That way, when looking at a character, we can know for sure how it should be pronounced, no matter where we're from or what language we use. The IPA assigns one single, different character to each sound used in speech, for all of the different sounds that get used in the world. To save us from this terrible fate, we have the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), invented in the late 1880s. But we need to be able to accurately capture all of the sounds that we hear! Otherwise, we can't say what's going on with phonetics or phonology, and we'll end up coming to the wrong conclusions about a whole host of phenomena. And languages that do a good job capturing their own sounds through spelling don't really manage to cover the sounds of other languages, or even of different dialects of their own language.

#IPA TALKING ALPHABET HOW TO#

English, like many other writing systems, isn't very good at working out how to spell things so that someone can easily know exactly how they’re supposed to be pronounced.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)